HRI teams with the Ocean Foundation, CubaMar to assess Cuba's Jardins de la Reina

As Cuba normalizes relations with the U.S. and seeks to expand its role in the Gulf of Mexico scientific community, HRI has stood ready to establish partnerships and launch new projects with the island nation. One of the few academic institutions licensed to work in Cuba, HRI has been engaged with the Cuban marine science community since its inception in 2002. One of our first initiatives is a Furgason Student Workshop on International Management (SWIM) that will examine issues of tourism and environmental conservation as Cuba's pristine environment faces a sharp increase in visitors. HRI Executive Director Dr. Larry McKinney and a team of HRI researchers recently traveled to Cuba for a field excursion and brought back this report.

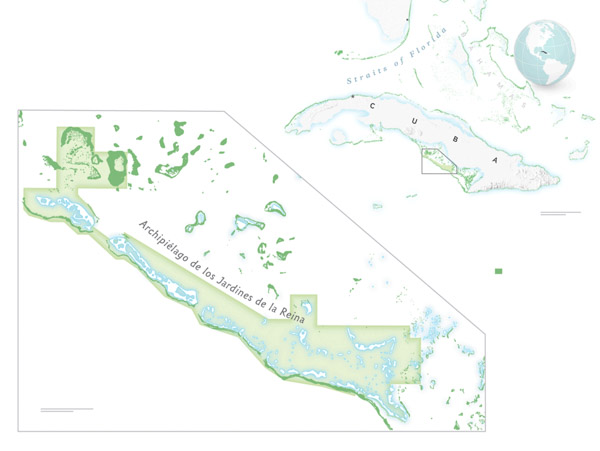

The Jardines de la Reina (Garden of the Queens) is one of the most significant marine parks in the world and one of Cuba’s natural treasures, covering some 840 square miles of coral reef and protected waters behind an archipelago of mangrove dominated islands surrounded by vast areas of seagrass.

The week of Feb. 10-17, HRI teamed up with the Ocean Foundation and CubaMar on a site visit to the Jardines de la Reina to assess conservation efforts, review management strategies for SCUBA and fishing in the park and look for potential sites for cooperative research with Cuban colleagues and institutions.

The park is very isolated and getting to it is a significant exercise. We chose to fly into Camagüey, take a two hour cab ride (even our driver got lost!) to the small fishing village and port of Júcaro, where Avalon (the Italian company with diving and fishing concession for the garden) bases it ships. Next is a four hour cruise to the Avalon field base on the inside edge of the archipelago. There we used the Halcón, a live aboard ship for our nine person team to explore the park over a four day period.

The coral reefs are as spectacular as described, an interesting combination of hard and soft corals mixed with algal growth. They are similar to other Caribbean reefs but for the abundance of large fish, especially sharks and grouper. The scale is also impressive and the obvious lack of diving and fishing pressure is abundantly clear. You do have a strong sense of isolation diving there and the reef structures, buttress, walls and canyons are massive. It was a special treat to snorkel above long stands of Elkhorn coral bordering reef tops such as I have not seen in the Caribbean for more than 30 years. Healthy and clearly expanding, it was overwhelmingly satisfying to see that sight! Very renewing. As wonderful as the reefs are, many of us we more impressed with the vast fields of seagrass. I saw only two prop scars the entire trip. If the seagrass were not impressive enough, the mangroves stole the show. In nearly fifty years as a marine biologist I have never seen such impressive stands. Their roots teem with millions of fish and invertebrates and their sometime 30 foot tall emergent structure support iguanas, many species of birds and even the weird Hutia, basically an arboreal “rat."

This a very special place and the Cuban government, and Avalon, are doing a fine job conserving and managing it. There are pressures from illegal fishing but no development pressure at all. My final thought as we cruised back from trip along the mangrove islands of the archipelago was that this was what the Florida Keys looked like before development — any development. I hope it stays that way.

Read more about our International Initiatives